Can money go 100x further overseas?

Most people don’t think about it often, but those in lower and higher income countries live dramatically different lives. One of the key differences? The amount you earn. Even after adjusting for cost of living differences, those in higher-income countries typically fall in at least the top 5% of income earners worldwide.

The scale of global income inequality is staggering — and it’s something we hope to reduce through initiatives like the 🔸10% Pledge. But there is one silver lining to the deeply unjust inequality we face: money often goes much further overseas.

This means that donations from those with more can have an outsized impact in places where resources are scarce, especially when it comes to global health and wellbeing.

The happy hour metaphor & the 100x multiplier

In his book Doing Good Better, Will MacAskill offers a useful thought experiment:

Imagine a happy hour where you could either buy yourself a beer for five dollars or buy someone else a beer for five cents. If that were the case, we’d probably be pretty generous—next round’s on me!

Will calls this idea the “100x Multiplier” — explaining that the average person in a rich country can likely do at least 100x as much to benefit those in lower-income countries than if they were to spend that dollar on themselves.

The “100x Multiplier” is a memorable way of illustrating the massive disparity in what money can do across borders. And when it comes to saving lives in the medical context, it may even understate the impact boost.

Think about this: it costs about $5 to buy and distribute a bed net that protects a child from malaria for years. When implemented at scale by an organisation like the Against Malaria Foundation, it costs on average around $5,500 to avert a death.

In contrast, preventing a single death in the US health system might cost hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars.

| Sub-Saharan Africa | US |

|---|---|

| ~$5500 saves a life through bednet distribution, in addition to preventing hundreds of malaria cases. Considered “cost-effective” as compared to other interventions. Source: GiveWell.org | ~$5.4 million saves a life through Medicaid expansion. Considered “cost-effective” as compared to other interventions. Source: Time.com |

In the case above, the cost-effective intervention in sub-Saharan Africa is 1000x cheaper.

.png?w=3840&q=75&fit=clip&auto=format)

Above: Net Assessment - Nigeria, Akwa Ibom state PDM18 (implemented by Society for Family Health). Image from Against Malaria Foundation.

That said, there are a few caveats to keep in mind when considering how much further your dollar can go when you donate it to programs in low-income countries. Before we get to those, let me explain one more piece of the underlying logic behind the 100x multiplier.

Log income utility

It’s a mouthful, yes. But the premise is actually pretty simple.

Basically, research into money and happiness strongly suggests that doubling someone’s income leads to the same increase in subjective wellbeing — regardless of the starting income.

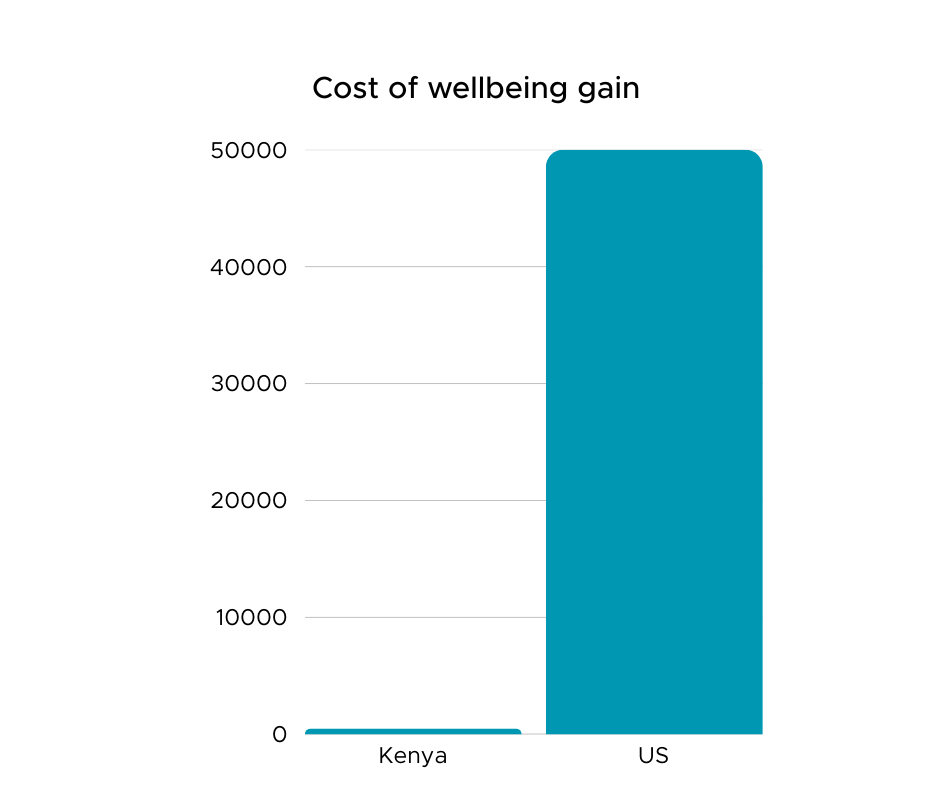

To make this concrete, imagine someone in Kenya is earning $500 per year. Another person in the U.S. is earning $50,000 per year. In one case, just $500 doubles someone’s income; in the other, doubling someone’s income would cost $50,000.

That’s already impressive. But it gets more so. Log income utility suggests that a doubling of income produces the same wellbeing boost — whether you paid $500 or $50,000 to do it. So effectively, this means you can achieve the same wellbeing gain in Kenya for 100x less than what it would cost in the US.

.png?w=3840&q=75&fit=clip&auto=format)

It’s pretty striking, but it also makes intuitive sense. Money matters more the less you have of it. So by extension, an increase in money also matters more.

The limits of the “100x multiplier”

While the 100x multiplier is a useful heuristic for showing just how much power money can have in lower-income countries, it shouldn’t be interpreted to mean that giving overseas is always 100x better. It also isn’t meant to be a literal estimate of the exact impact boost that giving overseas might produce. This is because:

Not all dollars translate directly into income gains. Effective charities often provide health interventions, not cash. Bed nets, deworming, and vitamin A don’t “double income” directly, so log income utility doesn’t directly apply. That said, as we saw above, these interventions do prevent illness & death for incredibly small amounts of money.

Countries are not homogenous. The power of a dollar may be different in Nairobi than it would be in a rural village.

Wellbeing is complex. Log income is a useful proxy, but it doesn’t capture everything. While research shows that increases in income are associated with greater life satisfaction, other important factors — such as safety, dignity, and systemic inequality — may fall outside the scope of this measure.

Interventions vary dramatically. Some effective interventions in lower-income countries are plausibly hundreds of times more cost-effective than common expenditures in rich countries (e.g. life-saving surgeries or late-stage cancer care). But not everything overseas giving does is 100x more impactful — it depends on the cause, charity, and intervention.

The bottom line

The “100x multiplier” doesn’t apply in every situation, but it captures a very real truth: our money can often achieve dramatically more when directed to the world’s poorest communities. Depending on the intervention, the difference in impact may be tenfold, fiftyfold, a hundredfold, or even greater. In some cases, 100x is actually a conservative estimate.

For those of us in wealthy countries, this means that where we give matters enormously. By directing even a small fraction of our income to highly effective charities working in global health and poverty alleviation, we can transform lives on a scale that’s hard to imagine — often far beyond what the same resources could accomplish at home.

Feel a strong pull to give locally? Read: Should charity begin at home?